First published

It was one of the most-discussed topics on Weibo and WeChat right before the Chinese New Year: the scandal involving Chinese blogging account ‘Mimeng’ (咪蒙), which sparked discussions on Mimeng herself and on the regulation and responsibility of ‘we media’ accounts on the Chinese internet.

Who or what is ‘Mimeng’? First and foremost, Mimeng is an online social media account with an enormous fanbase: 13 million followers on WeChat, 2.6 followers on Weibo.

The person behind the Mimeng blogging account is Ma Ling (马凌), a Chinese female author and Literature graduate who was born in 1976 in Sichuan’s Nanchong.

Over the past few years, ‘Mimeng’ has grown into a so-called ‘we media’ or ‘self media’ platform (zimeiti 自媒体), referring to private, independent, online publishing accounts that get their content across through blogs, podcasts, and other online channels. Mimeng is now more than Ma Ling alone: there’s an entire team behind it.

Mimeng has been controversial for years because of its clickbait titles and controversial stances on various issues. The topics most addressed in Mimeng’s publications are relationships between men and women, love, marriage, quarreling, and extramarital affairs.

Previous articles published by Mimeng, who is a self-labeled ‘feminist’ (and often mocked for it), include titles such as “This Is Why You’re Poor,” “Jealously Means Progress,” “I Love Money, It’s True,” “Men Don’t Cheat for Sex,” or “How to Kill Your Wife.”

Besides its content, there are also other reasons why Mimeng has triggered controversy in the past. The fact that Mimeng charges a staggering amount of money to advertisers, for example, is also something that previously became a topic of discussion – Mimeng allegedly charges some 750,000 yuan ($113,000) for a post mention.

SELLING FAKE STORIES

“As an influential We Media source, we must take on our social responsibility”

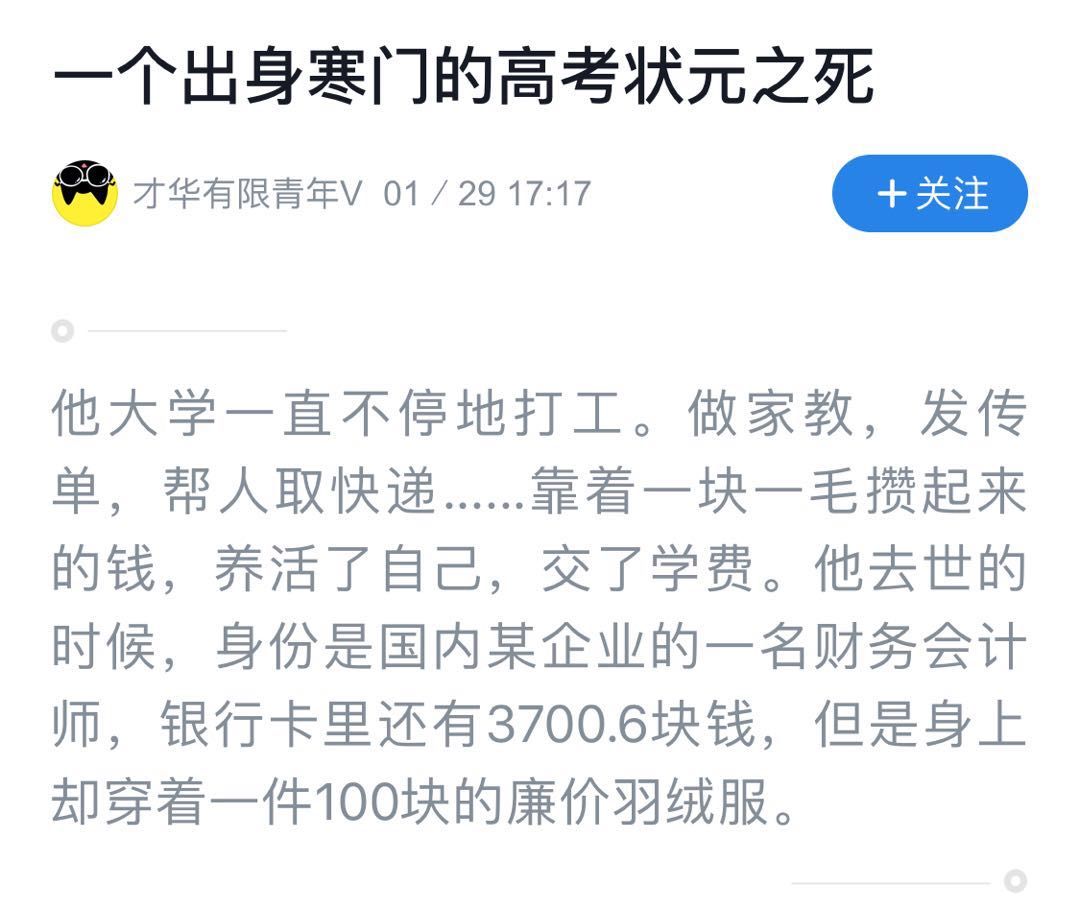

This time, however, Mimeng is hit by the biggest controversy thus far. The media group is under attack after publishing a story that turned out to be (partly) fabricated. The story was published on a WeChat account called Talented Limited Youth (才华有限青年), which is registered under the same legal entity as Mimeng. Its primary author, according to Sixth Tone, is a former intern of Ma Ling called Yang Yueduo.

The publication in question is a long story titled “The Death of a Top Scorer from a Poor Family” (“一个出身寒门的状元之死”) which allegedly portrayed the short life of the author’s old classmate: a young, bright mind, born in an impoverished family in Sichuan province. In the story, the protagonist did all he could to create a better life for him and his family.

He studied hard, got the best university entrance score of his city, and successfully graduated from university. But despite his efforts to start a life in the big city, he failed to succeed and tragically died of cancer at the young age of 24.

Shortly after publication, the moving and tragic story went viral on social media. However, several details made online readers doubt the story’s authenticity. It did not take long before readers proved that several aspects of the story were indeed untrue.

In light of the fake news allegations, Talented Limited Youth quickly deleted the story from WeChat. They also issued a statement defending the story’s authenticity, explaining that for privacy reasons, various details of the story were altered. According to Beijing News, Talented Limited Youth was then banned from posting on WeChat for 60 days.

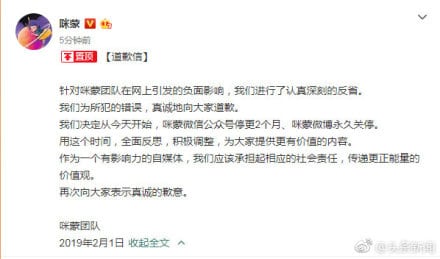

In response to the allegations, Mimeng offered its “sincerest apologies” on Weibo on February 1st, saying: “The Mimeng Group has decided to completely withdraw from Weibo and take a two-month break from WeChat. We will use that time to carry out serious and profound self-reflection.” The post continued saying that “as an influential We Media source, we must take on our social responsibility and pass on positive energy and values.”

The announcement went trending under the hashtag “Mimeng Shuts Down Weibo Indefinitely” (#咪蒙微博永久关停#), which has received over 210 million views at time of writing.

POISONED CHICKEN SOUP

“Mimeng, for you, patriotism is only business”

On social media, there is a clear divide between those who support and oppose Mimeng. While some are calling for a “complete shutdown” of Mimeng, there are also those who say they will keep on following Mimeng and that they enjoy their publications.

The controversial Mimeng account has even brought about a so-called “Following Mimeng Rate” (含咪率), a number based on how many of your WeChat friends are following Mimeng‘s public WeChat account (by checking Mimeng’s account on WeChat, WeChat users can see how many of their friends are following this account).

Mimeng opposers allege that the more friends you have that follow the Miming account, the more likely you are “to fail in life.”

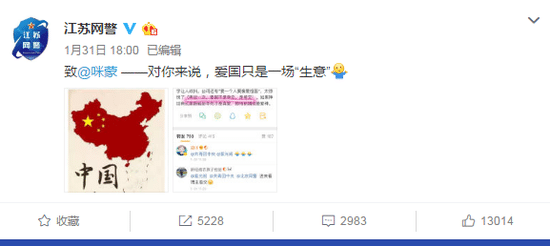

The official Weibo account of the Jiangsu Public Security’s Bureau of ‘Internet Safety’ (@江苏网警) is also a clear Mimeng opposer. Last week, they lashed out against Mimeng in a post titled “Mimeng, for you, patriotism is only business.”

The post hints at Mimeng’s inconsistent stance on patriotism, and it included screenshots from two earlier Mimeng posts from 2013 and 2016, one in which patriotism is referred to as a kind of “forced love,” and the other one saying: “I’ll love my country forever, its greatness will forever move me to tears.”

The post by the Jiangsu Bureau itself then also blew up on Weibo, with the hashtag “Jiangsu Internet Police calls out Mimeng” (#江苏网警点名咪蒙#) soon gaining over 210 million views. In the comment sections, many people criticize Mimeng for “deceiving people,” “promoting negative values” and “using anything to get clicks.”

One person wrote: “These self-regulated media only care about making money, they have no sense of social responsibility.”

Others said that the fake news story was nothing but ‘poisoned chicken soup’ (毒鸡汤).

This is a term that is often used to describe Mimeng’s content, and that of other self-media accounts, meaning that from the outside, it looks like “feel-good content” or “chicken soup [for the soul]” while it is actually ‘poisonous’ content with a marketing strategy or money-making machine behind it.

ZIMEITI CHAOS

“Self- media cannot become a spiritual pyramid scheme”

The Mimeng case has led to discussions in Chinese media on the status of ‘we media’ or ‘self-media’ platforms and their influence.

People’s Daily responded to the Mimeng scandal with a post on February 1st titled “Self-media Cannot Become a Spiritual Pyramid Scheme” (“自媒体不能搞成精神传销”), which argued that unless self-media accounts such as Mimeng actually work on establishing “healthy social values,” their apologies are only a way to temporarily dodge negative public attention.

In late January, Chongqing Internet authorities launched an investigation into 48 ‘self-media’ accounts, suspending two for spreading “fake news.”

State media outlet China News published an article, also this week, that describes ‘self-media’ as a ‘hypermarket’ where publishers will go to extreme measures, such as selling ‘fake news’ for clicks, spreading negative influences and anxiety among the people.

But these discussions are somewhat blurred, as it is not entirely clear what ‘self-media’ actually is in this context. Generally speaking, the term could include any micro-blogger who identifies themselves as ‘self-media’ or ‘we media’ (zimeiti 自媒体). But in the current discussion, it seems to only relate to those publishing accounts that have a certain influence on social media and the (online) media environment, posing a challenge to traditional news outlets.

Some definitions of Chinese ‘we media’ say it is basically is “an umbrella term for self-posted content on social media platforms” (Qin 2016; Jiang & Sun 2017) – this suggests that everyone who is active on WeChat and Weibo or elsewhere is basically in ‘self-media.’

A clearer description is given by Week in China, writing that “zimeiti typically operate as social media accounts run by individuals or as small firms established by a handful of former journalists.”

What makes it different from any other social media account, is that in ‘we-media’ or ‘zimeiti’ “the blogging has been professionalized and that the authors can make a living from it” (WiC 2018). It is a trend that has become especially visible in China’s online environment since 2012-2014.

This highly commercial side of ‘we media’ matters. If a publisher, such as Mimeng, charges advertisers exorbitant amounts of money, they also have to maintain a certain number of readers. They don’t just post as a hobby, it is serious business.

In a highly competitive online media environment, where hundreds of media outlets are fighting over the clicks of China’s online population of over 800 people, clickbait titles have almost become somewhat of a necessity for some of these publishers, with some even resorting to publishing “fake news” to get the attention – and the clicks.

China’s Newsweek Magazine (新闻周刊) calls the situation at hand a “self-media chaos” (自媒体乱象) that poses an “unprecedented challenge” for governing society in the 3.0 era. They call for “healthy development of self-media” and better legislation to control the mushrooming zimeiti, that, despite strong online censorship, are not as tightly controlled as China’s traditional media.

“Nowadays, we have less and less intellectuals, and more and more ‘people selling words.’ The chaos of self-media needs to be controlled,” one commenter on Weibo says (@ZY盒子).

But other people deem that readers themselves should pick what they read instead of authorities regulating it for them: “The important thing is that every reader must have the independence to judge for themselves [what they read]; just let the ‘poisonous chicken soup’ [naturally] lose their market.”

The Mimeng scandal shows that for social media accounts with a large following, one misstep can have huge consequences. This is something that Papi Jiang, a ‘self-media’ personality who became huge in 2015/2016, also experienced; she was reprimanded for disseminating “vulgar language and content” in April of 2016.

Very similar to Mimeng’s statement, Papi also issued an apology at the time, saying she supported the requirement for correction, and that she would attempt to convey “positive power” (正能量) in the future. “As a media personality,” she said, “I will watch my words and my image.” Papi’s CEO also expressed the company’s willingness to produce “healthier contents.” At the time, her videos were temporarily taken offline.

Meanwhile, some people think that the fact that Mimeng will stay silent for the coming two months is not necessarily a bad thing for the publisher: “They can take an extra long Spring Festival holiday.” As for Mimeng’s Weibo ‘holiday’ – that one is likely to be permanent.

By Gabi Verberg and Manya Koetse

References

-Qin, Amy. 2016. “China’s Viral Idol: Papi Jiang, a Girl Next Door With Attitude.” New York Times, 24 Aug https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/25/arts/international/chinas-viral-idol-papi-jiang-a-girl-next-door-with-attitude.html [2.6.19].

-Sun, Yanran and Jiang. 2017. “A Study on the Effectiveness of We-Media as a Platform for Intercultural Communication.” In New Media and Chinese Society, Ke Xue & Mingyang Yu (Eds.), 271-284. Singapore: Springer.

-WiC. 2018. “Headline earnings – Zimeiti hunt media profits but they still need to play by the rules.” Week in China, 15 June https://www.weekinchina.com/2018/06/headline-earnings/ [2.6.19].

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2019 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

The post Mimeng and ‘Self-Media’ under Attack for Promoting Fake News Stories to Chinese Readers appeared first on What's on Weibo.