On July 7th, 1937, an incident between Japanese forces and Chinese soldiers at Lugou Qiao, the Marco Polo Bridge in Beijing, led to the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), known in China as the Chinese War of Resistance Against Japan (中国抗日战争).

In China’s social media era, the anniversary of the Marco Polo Bridge has become an annual moment in which Chinese state media call on netizens to collectively remember July 7, spreading images and hashtags related to the incident.

An Important Bridge: What Happened on July 7?

While July 7, 1937, is commonly recognized as the start of the large-scale war between China and Japan, some historians consider the ‘Manchurian Incident’ of September 18, 1931, as the true beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War. This incident marked the establishment of the puppet government of Manzhouguo (Manchukuo) by Japan and its subsequent efforts to expand its influence in North China.

Lugouqiao (Marco Polo Bridge), image via Wikimedia Commons (source).

The Lugou (Reed Gulch) Bridge, also known as the Marco Polo Bridge, is a renowned historical river crossing located on the Yongding River. It was constructed between 1189 and 1192 during the Jin Dynasty and holds strategic significance south of the capital. The bridge is included among the ‘Eight Great Sights’ of Beijing due “the reflection of the moon at dawn on the Lugou Bridge,” as described in a poem written by Emperor Qianlong on the enchanting sight of the moon there. After Marco Polo praised the bridge in 1280 as “perhaps unequalled by any other in the world,” it gained fame in the West as the ‘Marco Polo Bridge’ (Knapp 2008, 46).

The Marco Polo Bridge Incident refers to the clash that happened on the night of July 7th, when a Japanese soldier stationed near the Marco Polo Bridge became separated from his unit. The Japanese troops assumed he had been captivated by Chinese and claimed to have heard shots, after which they demanded access to the nearby Wanping city, but were refused entrance. Although the ‘missing soldier’ later found his way back, the Japanese attacked the Chinese position (Lu 2019, 11; Schoppa 2000, 159; Vogel 2019, 248). This then turned into the first battle of the war, which would last eight years and would merge into World War II after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

Keeping the Memories Alive

Marking the 86th anniversary of the outbreak of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, the topic is top trending on Chinese social media. On Weibo, the hashtag “86th Anniversary of July 7th Incident” (#七七事变爆发86周年#), initiated by state media outlet Xinhua, received over 550 million clicks on Friday.

The hashtag page text says:

“86 years ago today, the Japanese aggressors, to achieve their evil ambitions to annex all of China through military force, shamelessly bombarded Wanping City, manufacturing the notorious Marco Polo Bridge Incident that shocked the world. 86 years have passed, and our country is doing good, but the national humiliation must not be forgotten. We will strive to become stronger!”

Another accompanying hashtag is “We Can Never Forget This Day 86 Years Ago” (#86年前的今天永远不能忘#).

A few sentences that are recurring throughout texts posted by Chinese state media outlets, as well as by netizens, are the following:

铭记历史 (Míngjì lìshǐ) – Remember the history

吾辈自强 (Wúbèi zìqiáng) – Strive to become stronger, strive to self-improve

勿忘国耻 (Wùwàng guóchǐ) – Never forget national humiliation

勿忘历史” (Wù wàng lìshǐ) – Never forget history

振兴中华 (Zhènxīng Zhōnghuá) – Rejuvenate China

The same kind of language is also often used to remember other parts of Chinese history that are included in the ‘Century of Humiliation’ (百年国耻) which includes, among others, the First and Second Opium Wars, the First Sino Japanese War, many unequal treaties, the Twenty-One Demands, and the Second Sino-Japanese War.

These historical events have especially become a major part of modern historical and popular consciousness in China since the 1990s and 2000s, after the Ministry of Education and Central Propaganda Department started prioritizing them in the formation of Chinese national memory and patriotic education (Ho 2021, 67-68)

In 1994, local governments were required to set up ‘patriotic education bases’ (爱国主义教育基地) as part of these efforts. On a national level, 100 patriotic education bases were set up, of which twenty were focused on the history of the Chinese War of Resistance Against Japan (2021, 68).

Near the Marco Polo Bridge, there is the Museum of the War of Chinese People’s Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (中国人民抗日战争纪念馆), one of the most important museums in mainland China commemorating the Marco Polo Bridge Incident and the Second Sino-Japanese War at large.

State Media Accounts’ Visual Propaganda

In the social media era, China’s patriotic education campaign is also modernizing and adapting to the behavior of China’s younger generations. A recent draft law submitted to the NPC Standing Committee for review calls for more online content and technologies aimed at spreading patriotism. The draft law requires online content providers to strengthen the creation, dissemination, and visibility of patriotic content (Zhuang 2023).

Although such laws can amplify the presence of patriotic and nationalistic content in the Chinese online environment, important historical dates like these already dominate the front pages of Chinese online state media platforms and are integral to online propaganda campaigns on social media apps.

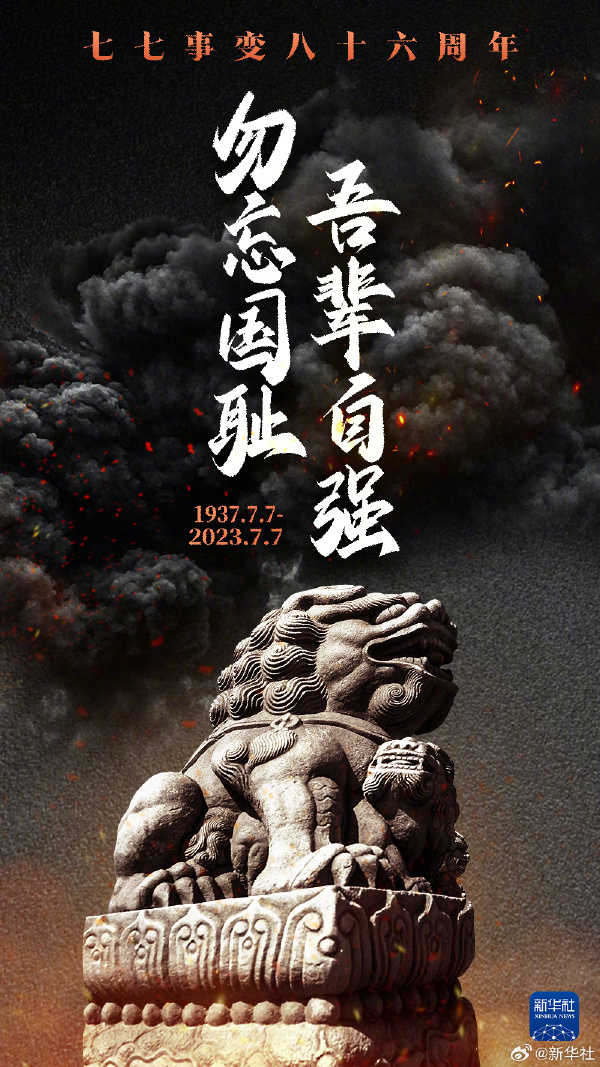

On this day, Chinese state media outlets are posting the same images on Chinese social media platforms as Weibo or Douyin.

The following are some of the most reposted images:

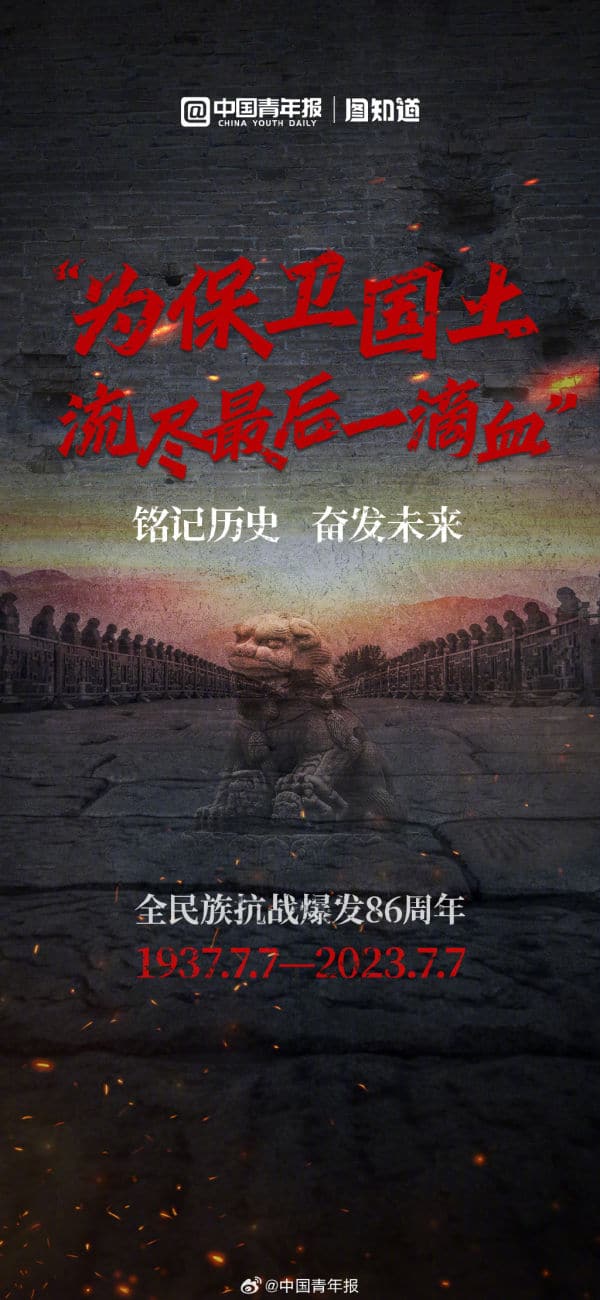

By China Youth Daily: This image shows the Marco Polo Bridge and its dragon statues, along with sparks flying around (animated on the Douyin site). The text reads: “Defend our homeland to the last drop of our blood!” (““为保卫国土流最后一滴血!”) This sentence was part of a manifesto issued by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China calling for a war of resistance after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident.

The sentence below says: “Remember the history, strive for the future” (铭记历史, 奋发未来).

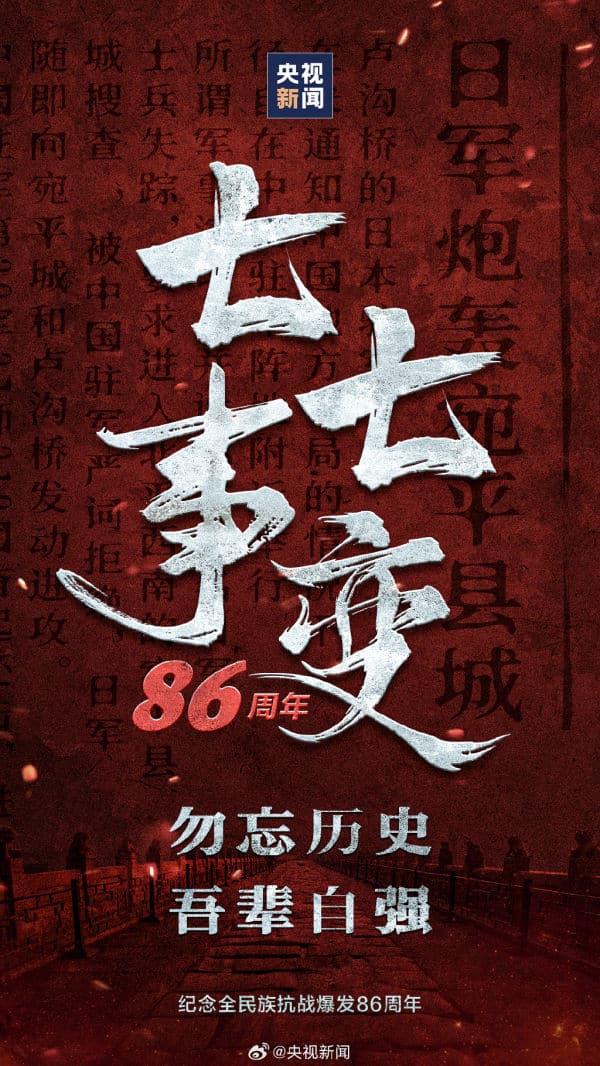

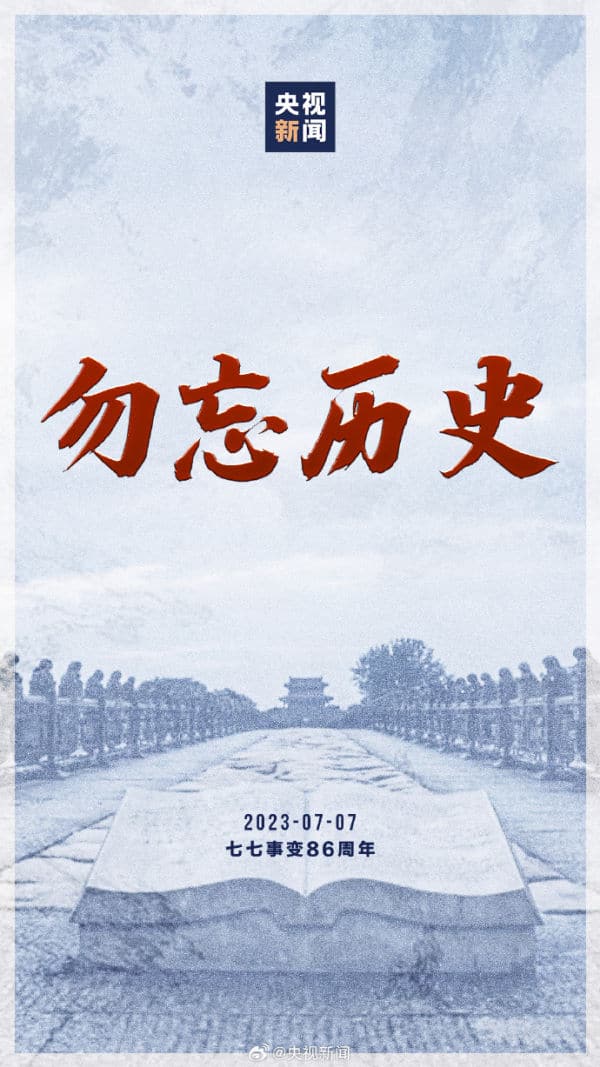

By CCTV: Both images contain the phrase “Do not forget history” (勿忘历史). The first image shows the characters for the Marco Polo Bridge Incident (“7.7. Incident” 七七事变).

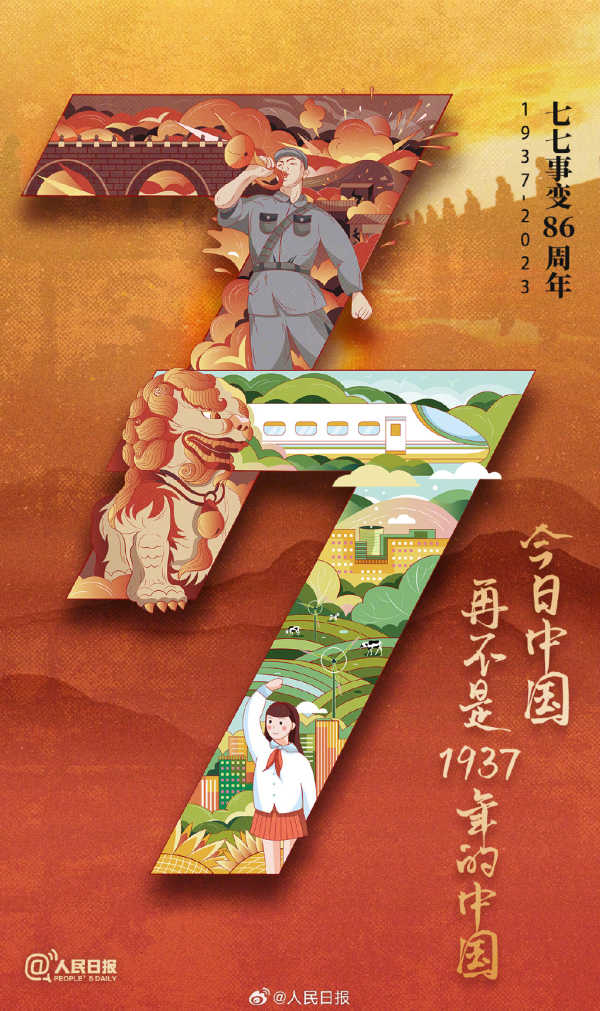

By People’s Daily: This image shows the 7.7 date, but accompanied by the text “Today, China is not the same as it was in 1937,” stressing the progress made by China in the past 83 years.

By Xinhua: Dramatized image of the Marco Polo Bridge, accompanied by the text “Never forget history, strive to be stronger” (勿忘历史, 吾辈自强).

What Are Common Reactions Online?

While many commenters echo the statements and phrases that are disseminated by Chinese state media outlets on this important historical day, there are also some Chinese social media users who are using this day to vent their negative feelings towards Japan.

This was also visible in 2022, when the assassination of Japanese former premier Shinzo Abe happened. At the time, one popular comment said: “Exam candidates, remember this for extra points: July 7 is the day of the 1937 Marco Polo Bridge Incident that started China’s War of Resistance against Japan; July 8 the day when Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was shot and killed.” The comment received nearly 100,000 likes.

Some share shocking pictures depicting the ‘Rape of Nanjing,’ a gruesome episode that occurred five months after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, and is widely recognized as one of the most horrific atrocities of the Second Sino-Japanese War. The massacre involved the mass murder of Chinese civilians by Japanese invaders during a six-week period from December 13, 1937, to January 1938.

At the Sihang Warehouse in Shanghai, people offered cigarettes and liquor to honor China's soldiers on the 86th anniversary of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, photo on Weibo by user @合肥兔曹君. pic.twitter.com/7TTDso2L74

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) July 7, 2023

Others also express the significance of commemorating the war and honoring those who lost their lives. One individual stated, “Even without social media, I would still remember this day. It has already been etched into the collective memory of the people.”

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

References

Ho, Wai-Chung. 2021. Globalization, Nationalism, and Music Education in the Twenty-First Century in Greater China. Amsterdam University Press.

Lu, Suping. 2019. The 1937-1938 Nanjing Atrocities. Singapore: Springer.

Knapp, Ronald G. 2008. Chinese Bridges: Living Architecture from China’s Past. Tokyo, Rutland, Singapore: Tuttle Publishing.

Schoppa, Keith R. 2000. The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. New York: Columbia University Press.

Vogel, Ezra F. 2019. China and Japan: Facing History. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Zhuang, Sylvie. 2023. “China to roll out patriotic education law for internet users, overseas Chinese and schoolchildren,” South China Morning Post, 26 June 2023 https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3225435/china-roll-out-patriotic-education-law-targeting-internet-users-overseas-chinese-and-schoolchildren [7.7.23].

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

The post “Never Forget July 7, 1937”: The 86th Anniversary of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident Remembered on Weibo appeared first on What's on Weibo.