On July 15, Wang Xiaochuan, the CEO of China’s search engine Sogou, posted an image of Winnie the Pooh on his Weibo account, writing nothing but “Little Pooh” along with it. Among his 2,7 million followers, around 500 people liked his post and over 200 shared it. Nothing special, it would seem – but over the past few years, Pooh bear has become more of a political meme in China than just a cute little Disney bear.

“You’ve got balls to post this,” one person responded. “Won’t this cause trouble for your company?”, others wondered: “Aren’t you scared to post something so sensitive?”

Over the weekend, rumors about Winnie the Pooh censorship circulated on social media in China as posts containing the bear’s name or image were taken down from Weibo and Wechat. It led many netizens to write about Winnie to test if their posts would be deleted.

“As I watched, I told my mother and father the similarities were uncanny.”

Although Financial Times reports about a thorough Winnie the Pooh “crackdown” in China, many of these posts also remain uncensored, triggering discussions on social media platforms about what is and is not ‘harmonized’ (censored).

“Obviously I can write [about Pooh], you can also find ‘Winnie the Pooh’ search results on Sina, and on video websites I can also see Pooh’s cartoons. Why don’t you first verify these things? I really hate this kind of fake news,” one annoyed girl wrote on Weibo.

“My posts about Winnie have already been removed 5 times, so it’s really true,” one other microblogger said. Many others also posted photos of how their Pooh-related content was being banned from Weibo and Wechat.

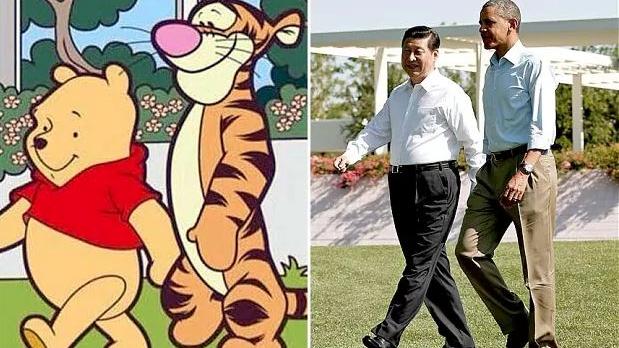

It is not the first time for Pooh to become a target for China’s online censors. It all started with an image of Pooh and Tigger in 2013, following the California summit between Barack Obama and Xi Jinping. Chinese netizens found a resemblance between the two leaders and the friends from the Hundred Acre Wood. The image soon went viral and was then taken down by censors.

In September of 2015, an image of Pooh became trending again on the day of the military parade. During the Beijing Parade that commemorated the 70th anniversary of WWII, President Xi Jinping drove around in a car (image), inspecting the troops. When someone posted an image of Pooh bear in a toy car, it was shared 62.000 times in little over an hour. Online responses included: “As I watched [the parade], I told my mother and father the similarities [between Pooh and the President] were uncanny.” The post was then soon deleted from Weibo.

Despite censorship – or actually because of it – a new political meme was born. Throughout the years, Pooh has resurfaced on Chinese social media at several times, also including other figures from the world of Pooh.

When President Xi had a somewhat chilly meeting with Japan’s Shinzo Abe in 2014, for example, an image of Eeyore and Pooh was shared online when netizens discovered another ‘eery resemblance.’

“An outcry against the very policies that forced it to become a secret symbol.”

This time, the resurface of Pooh seems to be more than just a humorous comparison to China’s president: the bear has become a symbol of defiance against online censorship. Had his image never been censored in 2013 and afterward, it would not carry the meaning it has today. Posting about Pooh is now showing resistance and messing around with China’s army of online censors.

In this way, Winnie the Pooh is somewhat similar to the Grass Mud Horse, one of China’s most famous memes. The 3-character phrase ‘cao ni ma’ (草泥马) literally means ‘grass mud horse’, but is pronounced in the same way as the vulgar “f*ck your mother” (which is written with three different characters).

In 2009, the ‘grass mud horse’ became some sort of mythical creature that resembled an alpaca. Everyone knew that it was actually a big middle finger to the authorities; it was netizen’s way of showing censors that they could avoid them through creativity. Chinese artist Ai Weiwei ‘adopted’ the ‘cao ni ma’ grass mud horse, spreading images of himself riding it, or holding it in front of his private parts.

According to An Xiao Mina in “Batman, Pandaman and the Blind Man: A Case Study in Social Change Memes and Internet Censorship in China,” the grass mud horse became “an outcry against the very policies that forced it to become a secret symbol” (2014, 361). Similarly, it is also the somewhat bizarre ‘bear hunt’ for Winnie that has given the character its new status on Chinese social media.

“What did Winnie the Pooh ever do wrong?!”

Pooh’s resurface comes at a time of tightening censorship. The recent death of Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo has added to the crackdown of any potentially politically sensitive content on Chinese social media.

For many netizens, posting about Winnie has simply become a game. “Why is the name Winnie the Pooh being censored? Hahahaha!”, some post, with others replying with just the name “Winnie the Pooh” to see how quickly their posts will disappear. “I heard the word Winnie the Pooh has been banned so I am just writing this post to check it out,” many people write.

But there are also people who are angered over the alleged ban on Pooh: “What on earth has Winnie the Pooh ever done wrong!?”

“See you next time, Winnie,” some netizens write, posting a picture of Piglet hanging up a picture of Pooh.

Some commenters think Pooh might not be back on Weibo anytime soon. They post his image and say goodbye for now: “Let’s say farewell to Winnie the Pooh.”

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

References

Mina, An Xiao. 2014. “Batman, Pandaman and the Blind Man: A Case Study in Social Change Memes and Internet Censorship in China.” Journal of Visual Culture, 13(3): 359–375. http://doi.org/10.1177/1470412914546576

©2017 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

The post Winnie the Pooh on Weibo – from Cute Bear to Political Meme appeared first on What's on Weibo.