What were the most discussed topics on Weibo of 2021? Here is an overview of top stories on Chinese social media from A to Z: a look back at the biggest trends on Chinese social media in 2021.

This is the “WE…WEI…WHAT?” column by Manya Koetse, original publication in German by Goethe Institut China, visit Yi Magazin: WE…WEI…WHAT? Manya Koetse erklärt das chinesische Internet.

The year 2021 has been quite a tumultuous one on Chinese social media. It was not just Covid19 that was among the biggest trends once again, it was also a year in which the 100th anniversary of the Communist Party, heightening tensions with the U.S., and national disasters such as the floods in Henan played a major role. But besides all the big topics, there were many smaller topics that became the biggest.

To give you more insight into the topics that went trending this year and which were most discussed by Chinese netizens, we have compiled this list of Weibo trends for you, from A-Z.

A is for: Alaska Talks

![]()

The U.S.-China strategic talks in Anchorage were a big topic of discussion on Chinese social media in March of 2021. It was the first major face-to-face U.S.-China meeting of the Biden administration, and due to the sometimes-angry words exchanged between the two sides, some called the Alaska talks a “diplomatic clash.”

While international media focused on the meeting and what their outcome meant for Sino-American relations and the foreign strategies of China and the U.S., many Weibo users instead focused on interpreter Zhang Jing (张京) who fiercely took notes while top diplomats Wang Yi (王毅) and Yang Jiechi (杨洁篪) were talking and flawlessly managed to translate their lengthy speeches.

Another moment that went viral online was when Yang Jiechi remarked he had instant noodles for lunch. Chinese state media outlet CGTN published a short video showing the Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi and Yang right before entering a session of the high-level talks, with Wang asking Yang “Have you had lunch?”, and Yang then answering: “Yes, instant noodles.”

![]()

‘Noodle gate’ went trending as a sign of American lack of etiquette: no formal dinner was arranged for the Chinese diplomats, and even with Covid19 restrictions, many netizens thought the Americans could and should have done more to accommodate their Chinese guests.

B is for: Battle at Lake Changjin

![]()

The Chinese blockbuster Battle at Lake Changjin that hit cinemas in the fall of 2021 became one of China’s highest-grossing films ever, breaking all kinds of box office records. The movie provides a Chinese perspective on the start of the Korean War (1950-1953) and the unfolding of the battle of Chosin Reservoir, a massive ground attack of the Chinese 9th Army Group against American forces.

The movie was a major topic on Chinese social media this year, not just because of its unparalleled budget, all-star cast, and production team, but also because its specific narrative of China’s ‘glorious victory’ at Chosin resonates with many Chinese in a time of growing nationalism and heightening international tensions.

Many social media users showed how emotionally engaged they were in the film by sharing their watching experience and posting photos and videos of their cinema visit. Some netizens even consumed frozen potatoes while watching the film as a sign of solidarity for the Chinese soldiers at the front for whom frozen potatoes were all they had to eat. Other filmgoers even saluted to the screen to honor those who lost their lives during the battle.

Read more about this topic here in English or in German.

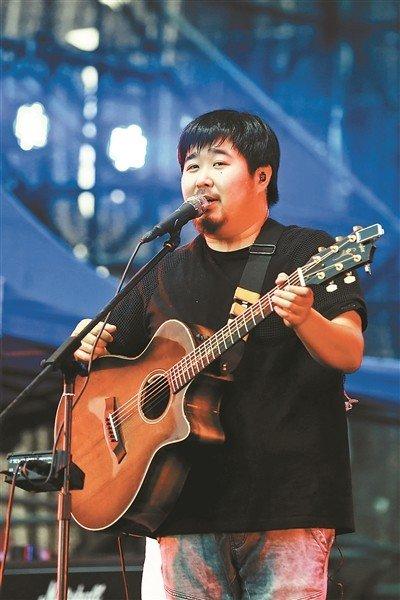

C is for: Call me By Fire

![]()

The all-male reality show Call Me By Fire (披荆斩棘的哥哥) was one of this year’s hit shows, with one Weibo hashtag dedicated to the show receiving a staggering 12 billion views.

Call Me By Fire featured 33 male celebrities, and the show received a lot of attention for various reasons. Participant Li Chengxuan (李承铉/ Nathan Lee) triggered discussions by speaking up about being a full-time father and suffering from depression. The 55-year-old Taiwanese singer Terry Lin Zhixuan (林志炫) was also a contestant and fell off the stage while filming. Another celebrity on the show, Chinese singer Huo Zun (霍尊), withdrew after his ex-girlfriend accused him of being a cheater and leaked WeChat conversation screenshots to prove that he actually disliked the show.

The Cantonese-speaking celebrities who were on the show also caused a social media sensation, contributing to an increased social media interest in the Greater Bay Area.

D is for: Dearest

![]()

The Chinese film Dearest (亲爱的) from 2014 received attention in 2021 again after a real-life development took place in the story that was the main inspiration behind the film.

Dearest is centered around a divorced couple in Shenzhen dealing with the disappearance of their son. The movie is partly based on the true story of Sun Zhuo, who was abducted in 2007 at the age of 4. His parents never gave up hope they would see him again and sacrificed everything to be able to fund their search efforts.

After a years-long search, Sun was finally found in 2021 due to the help of authorities and face recognition technology that helped trace the person suspected of abducting him. But in a perhaps unexpected twist, Sun stated that he would prefer to stay with his adoptive parents, who had raised him for over 10 years.

The story triggered many online discussions and raised more awareness on the issue of abducted children in China in times of the country’s one-child policy. Sun’s father spoke to the media saying: “For 2022, my biggest wish is that all the abducted children can finally be found.”

E is for EDG Championship

![]()

People all over China were overexcited to see China’s Edward Gaming (EDG) team win the League of Legends World Championship (Worlds 2021) title in November of 2021. With the hashtag “EDG Wins Championship” (#EDG夺冠#) getting over 3,7 billion views on Weibo, many netizens saw the success of the Chinese e-sports team as one of the highlights of the year.

After the victory of Invictus Gaming in 2018, EDG is the second Chinese team to win the world championship tournament of League of Legends (LoL, 英雄联盟), an online multiplayer video game in which two teams strategically compete by gaining more strength through the accumulation of items and experience over the course of the game to destroy the other team’s base. EDG managed to beat their notoriously strong South-Korean opponents in the exciting finale.

![]()

Chinese students who had promised to run around naked if the EDG team would win did so on the night of November 7.

Videos showing Chinese college dorms going crazy over the championship circulated all over social media. Some students in Xianyang got so carried away by the team’s miraculous win that they went as far as replacing the national flag in front of their college with the EDG team flag. Others also went a bit too far in celebrating their win; since they promised their friends that they would do things such as run around the school naked or have a sip of toilet water if China would win the World Championship, the most bizarre scenes unfolded across Chinese campuses.

F is for Floods in 2021

![]()

Various regions across China saw torrential rainfall and devastating flooding in 2021. Some of the most disastrous floods took place in Henan province in July, where Zhengzhou city and surrounding towns and villages faced the strongest rainfall ever recorded.

Amid the floods, some terrible scenes went trending on Chinese social media, such as the critical situation that unfolded in Zhengzhou Metro Line 5, where some 500 passengers got trapped inside trains with water reaching up to their necks. Rescuers arrived at the scene to help people escape, but 14 people did not make it out alive.

In Henan alone, the floods left more than 300 dead. Besides Henan, Hubei province, Sichuan, Shanxi, Hebei, and other areas were also struck by heavy rains and flooding. In Shanxi, more than 1.76 million people were affected by severe flooding.

For more about the role social media played in times of China’s flood disaster, read our article here in English or in German.

G is for Gansu Marathon

![]()

What was supposed to be an exciting ultramarathon race turned into a terrible tragedy in May of 2021 in Gansu’s Baiyin, where 21 runners died on a mountainous high-altitude track under extreme weather conditions.

The May 22 long-distance race started in the morning with 172 participating runners. Although all the runners had to have recent experience in running such a long race, they were not prepared when they encountered hail, freezing rain and strong winds during the afternoon. Many runners were just dressed in shorts and t-shirts, and the insulation blankets that they carried were insufficient to protect them from the sudden drop of temperature in the mountains. Although 700 people were involved in a rescue operation, 21 people did not make it out alive.

![]()

Runners who were freezing on the mountain shared photos on social media as the disaster played out in real-time on that terrible day.

The Gansu Marathon was a major topic on Chinese social media in 2021, not just because of the tragedy itself but also because people wanted to know who was to blame: was it a man-made disaster, or a natural catastrophe?

As a bright spot in this terrible story, there were the local shepherds who rescued many runners on the mountain by carrying them inside their huts and offering them shelter and warmth. At the end of the year, Chinese media and netizens are still reflecting on the stories of those villagers who saved the lives of many runners that day.

H is for Hongxing Erke

![]()

Image via Ellemen.

Nobody could have expected that Chinese brand Hongxing Erke (鸿星尔克, a.k.a. Erke) would become one of the country’s most popular sportswear brands in 2021. After all, Erke was only known as a relatively low-profile brand that seemingly was not doing too well over the past few years, especially compared to the bigger international brands and domestic sportswear brands such as Lining or Anta.

This all changed in late July of 2021, when the domestic sportswear brand donated a staggering 50 million yuan ($7.7 million) for the Henan flood relief efforts. This attracted a lot of attention on Chinese social media since Erke was known as a relatively low-profile brand that seemingly was not making a lot of profit. After people found out that the company donated such a high amount of money to help the people in Henan despite its own losses, its online sales went through the roof; everyone wanted to support this generous ‘patriotic brand.’ While netizens rushed to the online shops selling Erke, the brand’s physical shops also ran out of products with so many people coming to buy their sportswear. One female sales assistant was moved to tears when the store suddenly filled up with so many customers.

The brand’s popularity only further grew when the company also donated one million yuan ($153,800) to help rebuild the Henan Museum after the floods. A picture posted by Henan Museum on its Weibo account showed that Erke put the donation in the name of “China’s netizens.”

Especially at a time when consumer nationalism and anti-American sentiments are growing – also negatively impacting the reputation of brands such as Nike – Erke has proved to be a big hit. The brand’s generosity, its nation-loving image, and the fact that it is “proudly made in China” have all helped build on its reputation and have made the sportswear ‘underdog’ the coolest brand of the year.

I is for Involution (内卷)

![]()

‘Involution’ (nèijuǎn 内卷) officially already was a top buzzword in Chinese media in 2020, but one scene from the Chinese TV drama A Love for Dilemma (小舍得) reignited online discussions on the concept again in 2021.

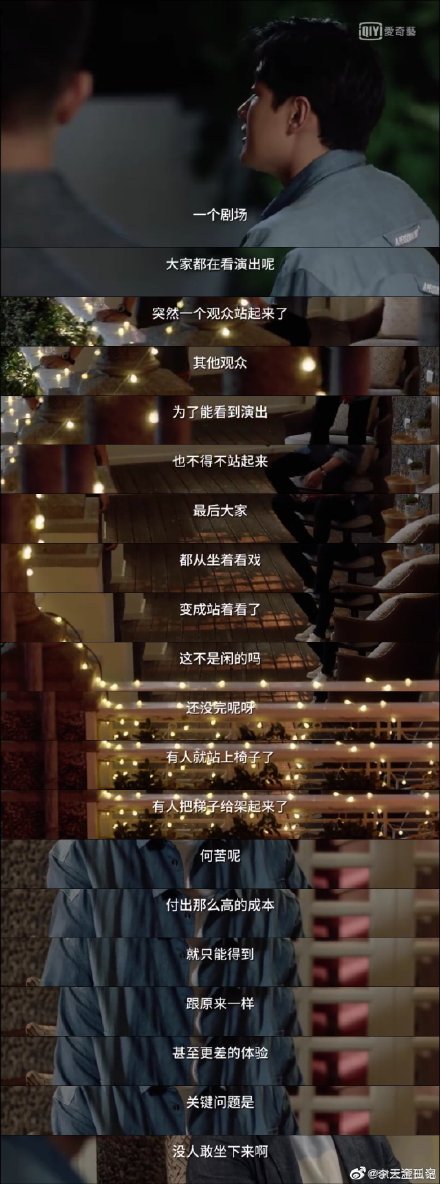

In the specific scene that went viral online, two male characters in the series discuss Chinese competitive society and its education system, saying it sometimes feels as if everyone is in a theatre watching a show together until one person stands up from their seat. This makes it necessary for other members of the audience to also stand up, until everybody is standing. The dialogue continues, with the two talking about how it does not stop at the people standing up. Because then there are those who will take it a step further and will stand on their seats to rise above the others. And then there are even those who will grab a ladder to stand higher than the rest. But they are still watching the same show and their situation has not changed at all – except for the fact that everybody is now more uncomfortable than they were before.

![]()

The dialogue from A Love for Dilemma in which the concept ‘Involution’ is explained.

The dialogue went viral for perfectly explaining ‘involution,’ the economic situation that occurs if, when the population grows, per capita wealth decreases. In China, this popular word has come to be used to represent the competitive circumstances in academic or professional settings where individuals are compelled to overwork because of the standard raised by their peers who appear to be even more hardworking, making life more difficult for everyone.

![]()

One viral image that captures the situation at hand is that of a Chinese college student who is working on his laptop while he is on the bicycle. In times of involution, there is always one person more competitive than the other!

J is for Justice for the People

![]()

Famous Chinese producer Li Xuezheng became a hot topic on Chinese social media in late 2021, when he publicly questioned the authority of China’s Association of Performing Arts (CAPA) in issuing a blacklist of online influencers and celebrities.

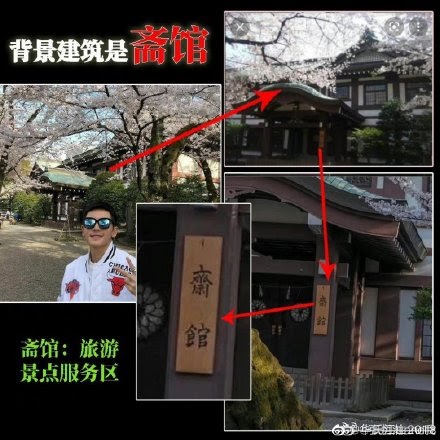

One of the names CAPA put on their so-called ‘warning list’ is that of Chinese actor Zhang Zhehan (张哲瀚), whose online photos from him visiting the area around the controversial Yasukuni Shrine in Japan in 2018 got him into trouble in the summer of 2021.

Li Xuezheng’s main stance is that, although he says he supports the general initiative of making blacklists, he wants to know how, why, and if CAPA has the legal authority to ban Chinese celebrities from the industry. Li stresses that China is a law-based society and that these kinds of punitive measures should have a legal basis. His mission is therefore hashtagged “Justice for the People” on Weibo (#人民的公义# “public justice for the people”), which has since received over 5 billion views. Li, who says he’ll support actor Zhang Zhehan in filing a lawsuit, is praised by many as a courageous man who is not afraid to question authorities.

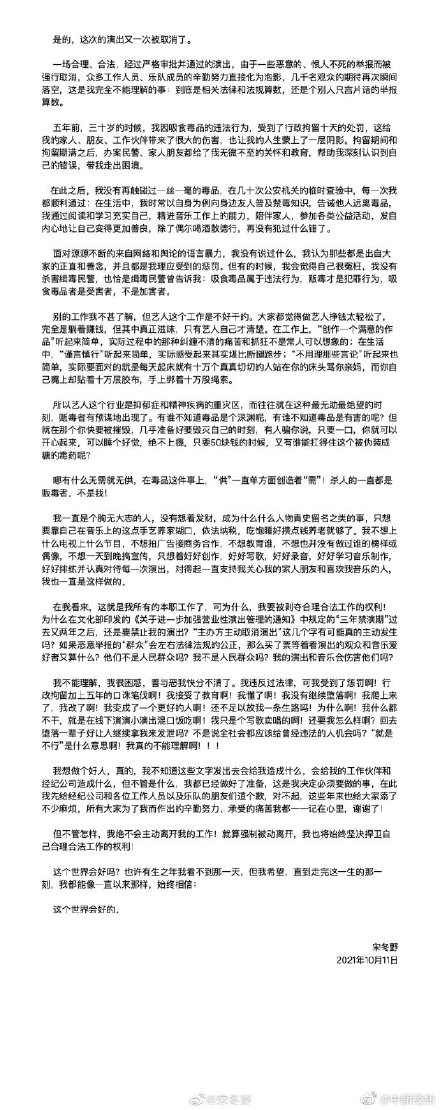

K is for Kris Wu

![]()

The Chinese-Canadian superstar Kris Wu, better known as Wu Yifan (吴亦凡), dominated Chinese social media in the summer of 2021, with news of his detainment over rape allegations leading to an explosion of comments on Weibo.

The 19-year-old student Meizhu Du (都美竹) was the first to accuse Wu of predatory behavior online, with at least 24 more women also coming forward claiming the celebrity showed inappropriate behavior and luring young women into sexual relationships. Although Wu denied all allegations, more than a dozen firms either cut ties or terminated contracts with him. As the scandal unfolded, various hashtags related to the story received billions of views on Weibo. Wu was formally arrested on suspicion of rape in mid-August 2021.

Although the Kris Wu scandal was somewhat of a social media earthquake already, his detainment was just the beginning of a summer filled with celebrity scandals.

L is for Li Ziqi

![]()

Li Ziqi, image via the Paper.

Li Ziqi (李子柒) is a Chinese internet celebrity who has been active as an online influencer and lifestyle vlogger since 2015, focusing on traditional Chinese foods, agriculture, tea, nature, and handicrafts. She has a Douyin channel with 55 million fans, a Youtube channel (16.5 million subscribers), and an e-commerce shop. Her videos are known for being very calm and soothing, showing Li preparing food in her hometown in Sichuan while birds are singing in the background, featuring beautiful scenes from nature and relaxing music.

Li was also called a “Chinese soft power ambassador” for having the most popular Chinese channel on YouTube, showing the beauty of China to the world. She was previously even named as one of the Top 10 Women of China and has become a cultural ambassador for Sichuan’s agriculture.

But Li’s regular content uploads were halted in the middle of 2021, when the social media star allegedly ended up in a legal battle with her company’s co-investors over shares and dividend payouts. Her Weibo has not been updated for months, neither has her Douyin or Youtube channel. The sudden video stop caused speculation and concern online – why was Li not posting anymore? Was she in trouble? Is she being silenced? Hopefully, 2022 will bring more answers and new Li videos about idyllic agricultural life.

M is for Meng Wanzhou

![]()

Nearly three years after the CFO of Huawei and daughter of Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei (任正非) was first detained in Canada during transit at Vancouver airport at the request of United States officials, Meng Wanzhou (孟晚舟) returned to China in 2021.

Meng Wangzhou was accused of fraud charges for violating US sanctions on Iran. Ever since late 2018, Chinese officials were demanding Meng’s release and called the arrest “a violation of a person’s human rights.” Meng was under house arrest in Vancouver while battling extradition to the United States.

Meng’s return home became a major topic on Chinese social media, where the Weibo hashtag “Meng Wanzhou About to Return to the Motherland” (#孟晚舟即将回到祖国#) received nearly three billion views, with thousands of netizens welcoming Meng back home.

While Meng returned to China, Canadian nationals Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, who were both arrested in Beijing in December of 2018 on suspicion of espionage, also returned home to Canada. While Meng’s return triggered thousands of posts and comments on Weibo, the release of Kovrig and Spavor did not get nearly as much attention.

N is for Nine-Nine-Six (996) Working Culture

![]()

Working ‘996’ schedules, which means working from 9am to 9pm for six days per week, is a reality for many Chinese workers. In 2021, China’s strenuous 996 working culture became a major topic of discussion.

Earlier in 2021, tech giant Pinduoduo made headlines when two of its young employees passed away. The sudden death of a 22-year-old female employee was soon linked to the company’s overwork culture, and when a male employee committed suicide days later, more staff members started speaking out about Pinduoduo’s working culture, making 996 a hot topic.

In August of 2021, Chinese authorities issued a stern reminder to companies that 996 schedules are illegal, and tech companies such as Bytedance and Kuaishou also began to change their long working hours. Whether or not 2021 will go down in history as the year in which China’s 996 working culture ended, yet remains to be seen.

O is for the Olympics

![]()

The Olympics were a big topic on Chinese social media in 2021, not just because China’s hosting of the 2022 Winter Olympics is nearing, but also because of China’s success at the 2021 Tokyo Summer Olympics.

While online discussions especially became intense and often funny on Weibo when it came down to competitions between China and Japan, there were also Chinese female athletes who suffered cyberbullying because of their performances during the Olympics.

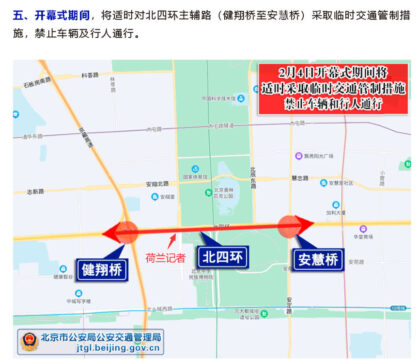

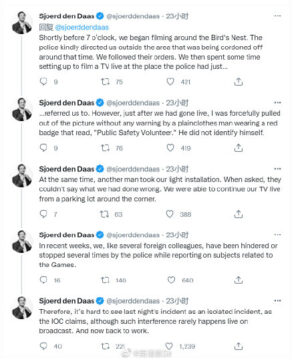

For the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics, the term “closed-loop management” (闭环管理) was introduced this year to describe the ‘biosecure bubble’ that will be established for all participants of the Olympics. It basically means that participants will only be allowed to move between Games-related venues for their training, catering, accommodation, etc. They will do so through a dedicated Games transport system.

Although the Olympics were already a big topic in 2021, it will also definitely become one of the bigger topics for 2022.

P is for Peng Shuai

![]()

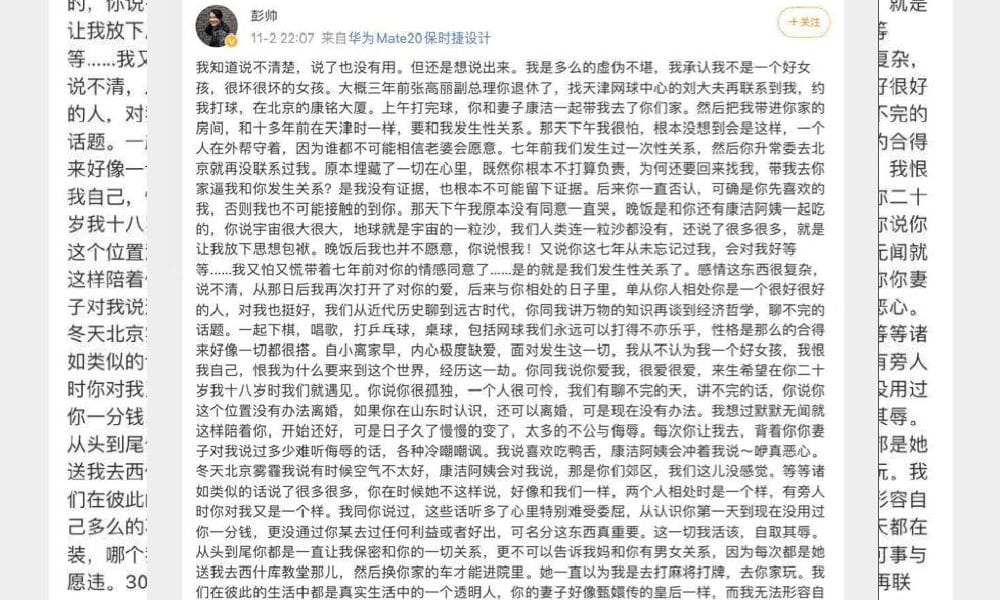

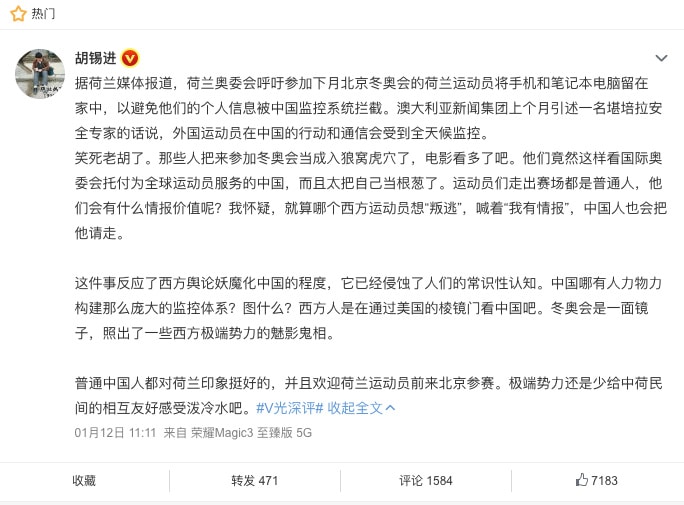

Peng Shuai (彭帅) is probably the biggest topic on Weibo that did not actually go trending this year, making her story a silent storm. In the night of November 2nd of 2021, a Weibo post by the 35-year-old Chinese tennis player sent shockwaves across social media.

In her lengthy post, the three-time Olympian describes details surrounding an alleged years-long affair she had with the married 75-year-old Zhang Gaoli (张高丽), who served as China’s senior Vice-Premier (2013-2018) and was also a member of China’s highest ruling council, the Politburo Standing Committee (2012-2017).

Although Peng’s post was only online for some thirty minutes before it was taken offline, screenshots already circulated on WeChat and beyond. When all discussions on the issue were censored, it triggered a wave of global concern about Peng’s wellbeing and whereabouts, which eventually also led to WTA announcing the suspension of all tournaments in China.

In December of 2021, Peng told a Lianhe Zaobao reporter at a Shanghai event that she has always been free and is not being monitored. Although Peng has appeared in public on multiple occasions, her name is still being censored on Chinese social media.

For a full translation of Peng’s post and a timeline of events, see our article here.

Q is for QR-based Society

![]()

Before the pandemic, QR codes were already used everywhere in China. QR codes are mainly used for mobile payments, but they are also often used for marketing purposes or to give people access to certain information or videos. Since the outbreak of Covid19, QR codes have become even more crucial in everyday life, since the Health QR Code System has become an important weapon in China’s fight against Covid19.

The first health code apps, developed by Alipay and WeChat, were launched in February 2020 to identify people’s risk of exposure to the virus and freedom of movement. The color-based code was soon assigned to some 900 million users in over 300 cities and became mandatory for those entering public spaces.

Health code apps work with three colors that are automatically generated based on the collected user’s data (including travel history, duration of time spent in risky areas, etc): green, yellow, and red. A green QR code allows an individual to travel within the city; a yellow one implies potential risks that require an at-home quarantine for 7-14 days; and a red code imposes a 14-day quarantine.

![]()

This year, “defending the green horse” (保住绿码) became a popular phrase on Chinese social media. The ‘green horse’ is a wordplay on ‘green QR code,’ which sounds the same (绿码). Since you can’t go anywhere if you’re not ‘riding’ that ‘green horse,’ netizens joke that defending the green horse is the most important task they have.

![]()

R is for Return Policy of Canada Goose

![]()

Canadian clothing brand Canada Goose caused major controversy on Chinese social media this year for its confusing and allegedly discriminatory return policy, which was found to be different in China than in other countries. Discussions on the issue flared up after the company reportedly refused to refund a customer in Shanghai for a damaged parka, stating that products sold at its retail stores in the mainland are non-refundable while Canada Goose allows a 30-day unconditional return outside of the mainland.

China’s Consumer Rights Protection Law stipulates that consumers should be allowed to return an item within seven days without giving a reason. Chinese netizens accused Canada Goose of double standards, not only for not even granting customers a seven-day period to return purchases, but also for making an exception to their worldwide 30-day return policy for mainland China.

The online anger over the Canadian fashion brand’s alleged discriminatory practices came in a year where foreign brands were already increasingly under fire due to international tensions and rising nationalism.

In response to the issue, Canada Goose changed its return policy in China and now promises free return and exchange services to mainland customers within 14 days after their purchase.

S is for Shanghai Red Mansion

![]()

The story of the ‘Shanghai Red Mansion’ caught the attention of thousands of netizens in late 2021, when a Chinese media outlet covered how dozens of women were forced into sex work inside a six-story building in the Yangpu district of Shanghai.

The Red Mansion has everything to do with Zhao Fuqiang (赵富强), a man who made headlines in September of 2020 when he appeared before a Shanghai court in relation to gang-related crimes. Zhao Fuqiang and 37 other defendants were found guilty of leading and participating in organized crime, rape, prostitution, fraud, bribery and corruption.

Zhao, who was given the death penalty in 2020, used threats and physical violence to get young, rural women to work for him. As an underworld kingpin, Zhao needed a safety net to protect him. At the so-called Little Red Mansion, Zhao would invite high-level governmental and businesspeople.

In December of 2021, China Business Journal (中国经营报) published an article detailing the the building and its layout, with many photos showing the extravagant rooms and peculiar layout design. Although the mansion has been closed since 2019, the shock was still big on social media, since the story did not come out until 2021.

The sentiment on social media was clear: if something big like this could happen in the busy center of Shanghai, with many officials being aware of it, what else is there that we don’t know?

For more on this story, check out our article here.

T is for Three-Child-Policy

![]()

2021 was the year in which Chinese authorities announced that all Chinese couples would now be allowed to have three children, with the topic immediately going trending online.

The last time the government announced a major shift in family planning policies was in 2015 with the end to the one-child policy. Although many people applauded the change, which allowed couples to have a second child, there were also those who thought financial burdens would hold people back from having a second child.

With the 2021 shift to a ‘three-child policy,’ many people also mentioned the economic burden that having more than two children would have on couples. A Weibo poll by Chinese state media outlet Xinhua asking, “Are You Ready for the Three Child Policy?” was ridiculed by some when nearly 30,000 people replied “I am not considering it [three kids] at all”, with only a few hundred people indicating a more positive stance on the policy. The poll was soon deleted.

Despite all the criticism and online jokes, there were also those who were genuinely happy that having three children would now be allowed for all couples. Recurring comments praised the freedom that comes with the loosening of family planning policies: “If you want to have more children, you can. If you don’t want to, you don’t have to.”

U is for Uploader Death Shocks Bilibili

![]()

There were some incidents in 2021 that showed how bloggers and online influencers can struggle with depression or other issues, also impacting those who follow them and creating more awareness on these issues.

One big story in 2021 involved the death of a so-called ‘uploader’ (called ‘UP’), a content creator, on the platform Bilibili. The blogger named ‘Mo Cha’ suffered from nasal tumors and other health problems. Although doctors advised that he needed to be hospitalized, he could not afford the treatment and surgery he needed. The impoverished young man also suffered from malnutrition, and often complained about his stomach hurting in online posts.

When it was verified that Mo Cha had died, social media saw an outpouring of expressions of sympathy and art dedicated to him.

Another big topic was that of a young Chinese woman who took her own life by drinking a bottle of pesticide during a live stream.

V is for Vaya

![]()

Viya is one of China’s most well-known and successful live streamers. In October of 2021, the ‘e-commerce queen’ made headlines when she managed to sell 20 billion yuan ($3.1 billion) in merchandise in just one live streaming session together with e-commerce superstar Lipstick King for a promotional event for Single’s Day.

In December of 2021, however, the successful online influencer made headlines for an entirely different reason, as it became known that she had been ordered to pay over 1.3 billion yuan ($210 million) in taxes, late payment fees, and other fines according to the Hangzhou Tax Administration Office.

Soon after this news came out, Viya’s livestreaming channels was suspended, and her social accounts on Weibo and video-sharing platform Douyin were also shut down.

W is for Wandering Elephants

![]()

A herd of wild Asian elephants that wandered hundreds of miles across southern China became a top trending topic on Chinese social media this year.

With much interest, netizens followed the journey of a herd of 16 elephants from their home in a wildlife reserve in mountainous southwest Yunnan province to the outskirts of the provincial capital of Kunming. Through drones that monitored and photographed the elephants, people enjoyed sharing the sometimes-heartwarming pictures of the wandering animals.

In September 2021, the elephants returned home after covering a total distance of 1,300 km.

X is for Xinjiang Cotton Ban

![]()

In March of 2021, the hashtag “I Support Xinjiang Cotton!” received over 6 billion views on Weibo after news came out that foreign brands including H&M, Nike and Adidas would no longer source cotton from Xinjiang over allegations of forced labor in the region. The move was part of a decision by the international NGO Better Cotton Initiative (BCI), which already announced it would cease all field-level activities in Xinjiang in late 2020.

The news was followed by a wave of social media boycott movements in China, with Chinese brand ambassadors cutting ties with international brands involved. Chinese e-commerce platforms Taobao, JD.com, Pinduoduo, Suning.com, and Meituan’s Dianping responded by removing H&M from their platforms.

Thousands of Chinese netizens supported Xinjiang cotton and those brands who still sourced their cotton from the region, with ‘patriotic’ brands on Taobao purposely starting to advertise their products as using “100% Xinjiang Cotton.”

Read more here.

Y is for Yuan Longping

![]()

Yuan Longping (袁隆平), also called the “Father of Hybrid Rice,” was a Chinese crop scientist who is famous for developing the first hybrid rice varieties in the 1970s. As someone who experienced the horrors of famine himself, Yuan’s development of high-yield rice hybrids made him a national hero in China, and he was credited with saving countless lives.

Yuan (1930) passed away on May 22 of 2021, and he was mourned by thousands of netizens online. As a key player in the Green Revolution, Yuan is honored as of China’s most famous and important scientists.

![]()

I Always Had Two Dreams” “我一直有两个梦想” by digital artist Wuheqilin.

Chinese netizens posted many images and art pieces honoring Yuan. The artist Wuheqilin, most famous for political satire mocking Western powers, also made a patriotic artwork dedicated to Yuan.

Z is for Zheng Shuang Surrogacy Controversy

![]()

In a year that was filled with celebrity controversies, one of the biggest was that of Chinese award-winning actress Zheng Shuang (郑爽) who got caught up in major controversy together with her ex-partner Zhang Heng (张恒) when a social media storm erupted in January of 2021. That is when rumors surfaced on Weibo and Wechat that the celebrity couple had separated and that there was a dispute involving two of their children born in the US through a surrogacy arrangement. The topic soon became known as the Zheng Shuang ‘Surrogacy Gate’ (郑爽代孕门).

Similar to other celebrity breakups that occurred in China recently, a lot of the developments in the divorce played out on social media – Zheng’s ex-partner posted about the situation on Weibo and it became clear that Zheng Shuang allegedly left him stranded in the United States with the two babies, unable to bring them back to China with him since she supposedly did not cooperate with the necessary legal procedures.

The scandal was just the beginning of Zheng’s unfortunate 2021 year. In light of the controversy, various brands ended their partnership contracts with the actress, and Zheng’s professional career suffered a major blow when Huading Awards announced it would revoke Zheng’s honorary titles, including former awards for best actress and favorite TV star. The celebrity was also boycotted by China’s State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television, and she was later ordered to pay a $46 million fine for tax fraud, before ending up on the blacklist of China’s Association of Performing Arts.

To read more about canceled celebrities check out our article here.

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

Featured image by Ama for Yi Magazin.

This text was written for Goethe-Institut China under a CC-BY-NC-ND-4.0-DE license (Creative Commons) as part of a monthly column in collaboration with What’s On Weibo.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

The post The ABCs of Weibo 2021: These Were the Biggest Trends on Chinese Social Media appeared first on What's on Weibo.