By Friday, April 15, a Weibo hashtag page about the U.S. being the worst country in the world when it comes to human rights (#美国就是全球最大的人权赤字国#) had received over 580 million views on Chinese social media platform Weibo.

The hashtag, initiated by Chinese media outlet CCTV, was posted in the context of a video report issued by the state broadcaster on April 14 regarding the U.S. Department of State’s 2021 Country Report on Human Rights Practices, which was published on April 12 (see the China section here).

CCTV argued that the U.S. report, like previous years, attacks and slanders China without properly shining a light on the human rights situation in the U.S., claiming that America is failing when it comes to respecting and protecting human rights.

The Sichuan Communist Youth League added: “In the name of ‘anti-terrorism,’ nearly a million lives were taken; in the name of ‘sanctions,’ human rights are violated. Who is actually hindering world peace?”

Why this particular hashtag attracted so much attention online was recently explained on Twitter by Wen Hao (文灏), a reporter at Voice of America. Wen Hao suggested that this hashtag, along with the phrase ‘Call Me By Your Name,’ was used by Chinese netizens to express their anger about Chinese official channels often using the United States as a bad example to distract people’s attention from what is going on within mainland China.

It's gone unnoticed by many. So I felt like I should properly document what just happened on Weibo today.

Netizens in China, for just a few hours, got to unleash their wrath on the Chinese government for how they handled the Covid crisis in Shanghai and other social issues.

— Wenhao (@ThisIsWenhao) April 13, 2022

Wen Hao reported how on April 14, in a time frame of some four to five hours, a flood of angry comments started criticizing the Chinese government for their handling of the Covid crisis and other issues under this hashtag, instead of actually attacking the U.S. according to the state media’s narrative.

Not long after, at around 4am, the only posts left using the hashtags were by verified and official accounts and the ‘Call Me by Your Name’ phrase no longer returned any results on the Weibo search function.

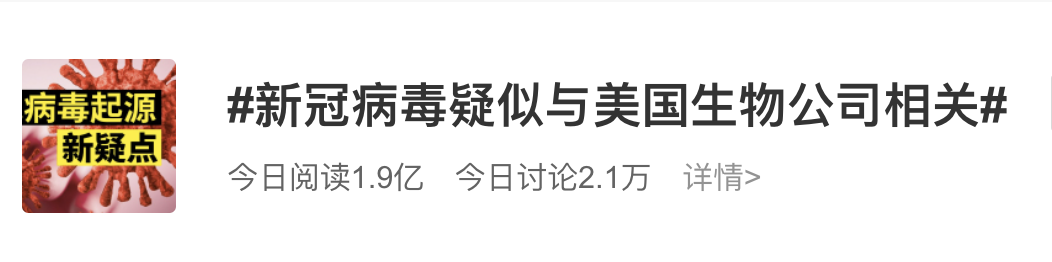

Chinese netizens then later jumped moved on to other hashtags, including one by state media outlet China Daily about how “Covid-19 is suspected of being related ot American bio companies” (#新冠病毒疑似与美国生物公司相关#), or one by Beijing Evening News about how “America’s murder rates are increasing at at an astonishing speed” (#美国的谋杀率正以惊人速度增长#).

Recently, Chinese state media also initiated another hashtag stating that an American company has created Covid19, which led to many netizens blaming Chinese official media for publishing misinformation (read more here).

Now, in the light of building frustrations and disbelief on how Shanghai has handled the Covid-19 outbreak, these state media-intiated hashtags are used to expose incidents in Shanghai and make critical views on China pop up on Weibo without immediately being censored.

Although the April 14 China Daily post about American companies being suspected of creating Covid-19 received over 20,000 replies, only a few comments were visible to Weibo users at the time of writing, but discussions continued in other threads and posts.

“Oh how scary America is,” some wrote, posting humorous memes.

“Are we doing another ‘Call Me By Your Name’ Campaign tonight?

The anti-American rhetoric propagated by Chinese media in hashtags – which make it to Weibo’s top trending lists – has kept attracting news posts voicing discontent on Chinese policies, with Weibo users mostly using sarcasm.

“The man-made virus is so scary, the America is responsible for everything,” one netizen wrote, posting various photos showing a community protest in Shanghai (read about that incident here)

“How horrible! We should let Ailing Gu come back before they use her for one of their experiments,” another netizen joked about the US-born Chinese Olympic star.

“Are we still doing another ‘Call Me By Your Name campaign’ tonight?” one Weibo commenter wondered in the early hours of April 16, referring to using state media hashtags calling out US to call out on China.

Call Me By Your Name (请以你的名字呼唤我) is, not coincidentally, also the title of an Oscar-winning movie featuring a homosexual relationship. In 2018, it was removed from the official program of the Beijing Film Festival after it did not get the approval from the censorship board. Despite the censorship, or perhaps also because of it, Call Me By Your Name reached somewhat of a cult classic status among some Chinese fan groups.

As explained by Wen Hao in this Voice of America article, the phrase has now become a catchphrase to voice dissent with how Chinese officials are often using ‘America is bad’ stories and hashtags to divert attention from things that are going on within their own country.

By now, hashtags such as #CallMeByYourName or #ChineseVersionCallMeByYourName (#中国版 Call Me By Your Name#) have all been removed from Weibo’s search results.

Discussions about La La Land (爱乐之城) were also censored on April 16 in light of the title being used to discuss sensitive topics.

Although many people say they appreciate the ‘Call Me By Your Name’ campaign, there are also some fans of the actual movies who aren’t happy about it: “Now we can’t even use these terms to discuss the actual films anymore!”

Chinese fans of the American movie Don’t Look Up (不要抬头) might be the next to find themselves unable to use the hashtag anymore, as some netizens are suggesting that will be the next title used for more discussions – until the next suitable state media hashtag comes along.

For more articles on the Covid-19 topics on Chinese social media, check here.

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our weekly newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2022 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

The post How Chinese State Media’s ‘America is Bad’ Hashtags Are Backfiring on Weibo appeared first on What's on Weibo.

) to refer to Covid-positive people.

) to refer to Covid-positive people.